-

In memoriam Miloš Forman

13.4.2018Ze Spojených států amerických přišla smutná zpráva. Dnes ve svých 86 letech zemřel zřejmě nejslavnější současný český filmový režisér, Miloš Forman, držitel dvou Oscarů za režii a tří Zlatých glóbů. Jeho prvním barevným a zároveň posledním českým filmem před emigrací do Spojených států byla hořká komedie Hoří, má panenko, natáčená v podrkonošském městečku Vrchlabí na počátku roku 1967. Dosud nikdy neuveřejné amatérské fotografie a natočený neseřazený filmový materiál z nátáčení tohoto filmu čekali na své první diváky více jak půl století. A proto jsme je k 50. výročí prvního uvedení Hoří, má panenko ve Vrchlabí zrestaurovali a zdigitalizovali na sklonku minulého roku.

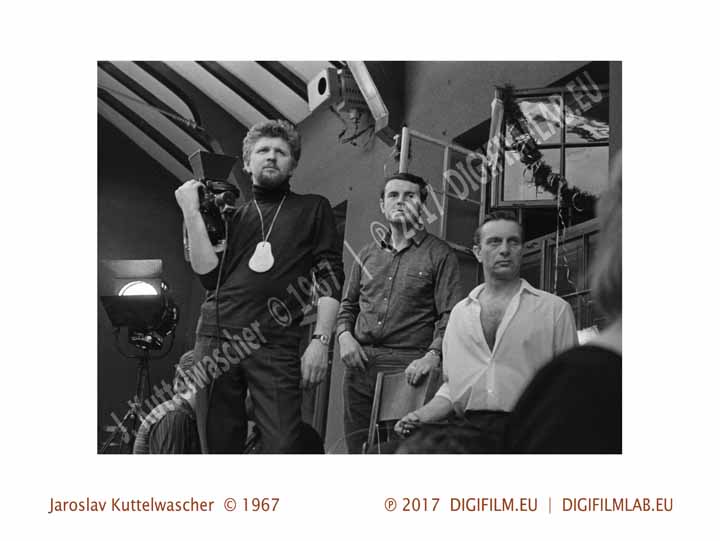

Na horní fotografii Jaroslava Kuttelwaschera z natáčení je vidět kameraman Miroslav Ondříček s kamerou, vedle něhož stojí režisér Miloš Forman, kterýnašel inspiraci k Hoří, má panenko spolu s se spoluscénáristy Passerem a Papouškem na hasičském bálu ve Vrchlabí, když předtím si v Itálii společně marně lámali hlavu se scénářem k nikdy nerealizovanému filmu Američané přicházejí, který si u nich objednal italský producent Carlo Ponti, bývalý provinční obchodník s těstovinami.

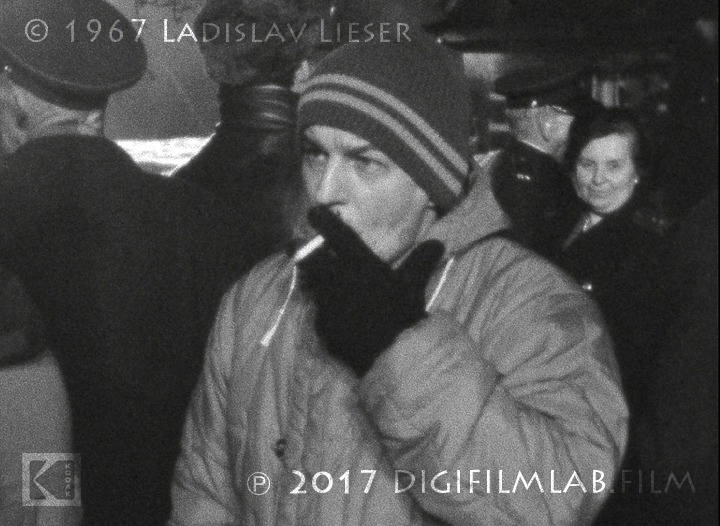

Na horním políčku si můžete prohlédnout poněkud nervózního Ivana Passera při nočním natáčení několikrát opakované scény s hořícím domem z dosud nikdy nezveřejněného amatérského 8mm černobílého nesestříhaného filmového záznamu Ladislava Liesera z natáčení Formanova filmu po více než 50 lety, který jsme zdigitalizovali a zrestaurovali...

...A kotouč za kotoučem, scénu za scénou jsme na objednávku autora a místní samosprávy tento filmový a nesestříhaný záznam z natáčení Formanova filmu ve Vrchlabí před více než 50 lety správně chronologicky serařadili, opatřili mezititulky a digitálně upravili, aby mohl být správně promítán i na moderních digitálních kinoprojektorech. A tak se v pátek 15. prosince 2017 povedlo uvést poprvé v digitální podobě nový Film o filmu Hoří, má panenko právě v kulturním domě ve Vrchlabí, kde se film Hoří, má panenko na počátku roku 1967 natáčel. Film doprovodila živá hudba z Big Bandu ZUŠ Karla Halíře z Vrchlabí.

Scénář k světoznámému filmu, který v dobové kritice označil spisovatel Milan Kundera „za neslušné manželství komična se smrtí“ sepsali ve Vrchlabí za šest týdnů a jeho natáčení v česko-italské koprodukci tu začalo 24. ledna 1967. Film byl natočení za několik málo měsíců. Vše šlo poměrně rychle i proto, že Carlo Ponti investoval do filmu přes 90 tisíc amerických dolarů a dodal českým filmařům nejen speciální kamerový vozík Elemack, umožňující rychlé a jakoby „dokumentární“ natáčení s neherci, který si můžete prohlédnout na následující fotografii Jaroslava Kuttelwaschera, kterou jsme zrestaurovali z originálního negativu 35mm kinofilmu Agfa.

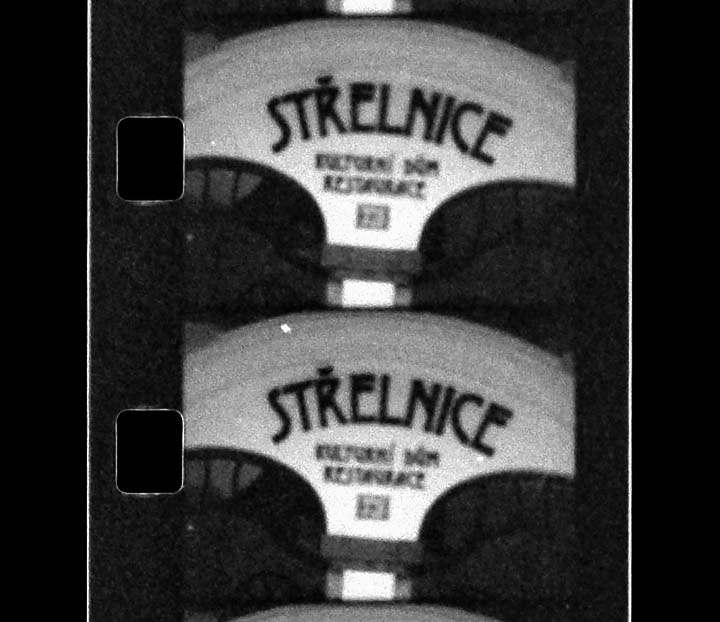

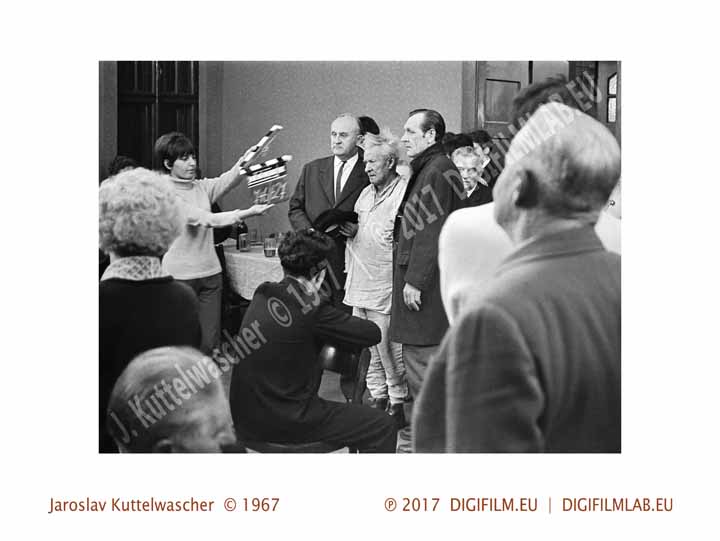

Kromě toho přivezl Ponti filmařům do Vrchlabí i 34 tisíc metrů devizové americké barevné suroviny Kodak Eastmancolor, který byl mnohem kvalitnější než kterákoliv jiná barevná surovina. Forman vzpomíná, že “chtěl film natočit barevně proto, aby se přiblížil realitě,“ a i proto dali filmaři před barrandovským ateliérem přednost vrchlabskému kulturnímu domu Střelnice. Formanův kameraman Miroslav Ondříček hledal tu správnou barevnost v amerických filmech a chtěl, aby převažovaly měkké, pastelové odstíny. S odstupem času na to vzpomíná slovy: „Zblbnul jsem z té barvy tak, že jsem chodil po Praze a sbíral podzimní listí, dokud jsem nenašel tu nádhernou hnědou.“ Nechal kvůli tomu i třikrát přemalovat sál, přešít hasičské uniformy na modrošedé a zakázal všem komparsistům nosit oblečení ve studených barvách. Zvukař Adolf Böhm zase nutil herce tančit na parketu v ponožkách, aby film měl i autentický zvuk, mohl snímat zvuk kontaktně a vyhnuli se dodatečnému ozvučení filmu ve studiu. Dechovka ale hrála stále, i když se nenatáčelo, "aby se lidé pořád cítili jako na skutečném bále," vzpomíná na natáčení režisér Forman. Ne všechny scény se ale točily v ponožkách a k některým se i proto musely dotáčet postsynchrony ve studiu, jak to ukazuje i následující fotografie.

Díky badatelskému úsilí našich výzkumníků se podařilo v roce 2011 během příprav digitálního restaurování Hoří, má panenko, v pořadí teprve druhé českého filmu, nalézt v barrandovských ateliérech 3. a 4. díl mixu filmové hudby Hoří, má panenko na 35mm perforovaném magnetickém pásu, který měl daleko kvalitnější zvuk než zbytek filmu, uchovaný jen na optickém záznamu zvukového negativu třetí generace.

I když byl film Hoří, má panenko nominován na cenu americké Akademie, Oscara, italský obchodník se špagetami však přesto nebyl spokojený, údajně kvůli kratší stopáži, ale ve skutečnosti proto, že film bylo podle něho „málo sexy“. A podle vzpomínek Miloše Formana ho prý chtěl přesvědčit: „že to chce víc lásky! Tím myslel nějakou nahotinku.“ A nebýt květnových stávek a zrušeného festival v Cannes v roce 1968, byl si z festivalu za film Hoří, má panenko odnesl Forman asi i Velkou cenu.

-

Digitalizace a restaurování Vašich dokumentů, filmů a fotografií profesionály za hubičku!

15.12.2017Vlastníte staré dokumenty, filmy nebo fotografie a rádi byste je nechali zdigitalizovat a zrestaurovat od profesionálů, kteří přednáší v oboru na univerzitách a spolupracují s národními archivy, muzei, galeriemi či knihovnami v ČR i v sousedních zemích? Ať už jste amatérským sběratelem, dědicem rodinné sbírky po prarodičích, anebo kurátorem místního archivu, muzea či kulturního domu, obraťte se na nás!

Vlastníte staré listinné dokumenty, archivní fotografie, nebo filmy jakéhokoliv formátu a kvality, a rádi byste je prezentovali v digitální a zrestaurované podobě svým přátelům, rodině, místní komunitě v místním muzeu, galerii, na výstavě v místním kulturním domě nebo škole, na internetu, televizi nebo digitálním kině?

V roce 2018 si připomeneme výročí 100 let od vzniku Československa a zároveň kulatá výročí 100, 80 a 50 let od historických mezníků připomínajíících události z roku 1938, 1968 i 25 let od vzniku samostatné ČR. Je ve Vaší sbírce předmět, který by připomínal Československo a rádi byste ho předvedli svým blízkým, místním spoluobračům nebo i širší veřejnosti? Proč jej stále uchováváte? Kdo byl jejich autorem? Komu patřil? Jaký je jeho příběh? Obraťte se na nás!Vlastníte staré dokumenty, filmy nebo fotografie a rádi byste je nechali zdigitalizovat a zrestaurovat od profesionálů? Kontaktujte nás emailem: PRODUKCE@DIGIFILMLAB.EU nebo telefonicky: 776 121212.

Prezentace naší práce ve formě projekce dosud nikdy nezveřejněného digitalizovaného krátkého filmu o filmu 'Hvězdy Miloše Formana' Ladislava Liesera a výstavy zrestaurovaných fotografií Jaroslava Kuttelwaschera z natáčení prvního barevného filmu a posledního českého filmu Miloše Formana 'Hoří, má panenko' proběhne v rámci oslav 50 let od natáčení filmu ve Vrchlabí ve dnech 15. - 17. 12. 2017.

-

Networking from digitisation to access

30.10.2015Central European Film Heritage Research, Promotion and Presentation | PRESS RELEASE

The sharing of experience, archival documents and the finding of solutions to shared technological, organisational and copyright issues in the digitisation and restoration of Central Europe’s film heritage is the subject of a research project whose other outcomes include the promotion of digitally restored archive films in the region, undertaken during individual presentations of the interim research results at international conferences.

The climax of the joint collaboration and research mapping both individual film collections and using the oral research method of interviewing experts from different countries in addition to the study of paper archives, was the autumn working meeting and workshop of film and photography restorers from Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the Slovak Film Institute’s Digitisation Workplace, during which separate digitisation projects were presented. Shared problems were also identified and new methods for dealing them in the future were proposed. One of the key outcomes was the regular undertaking of applied research into monitor prototypes for digital cinematography in collaboration with EIZO Europe, verifying their application in practice, in combination with non-dedicated film players in DCP (Digital Cinema Package) format, giving restorers in Central Europe access to more affordable standardised film presentations on new compact displays instead of the relatively expensive projectors used for digital cinematography, while maintaining international norms and standards.

The climax of the joint collaboration and research mapping both individual film collections and using the oral research method of interviewing experts from different countries in addition to the study of paper archives, was the autumn working meeting and workshop of film and photography restorers from Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the Slovak Film Institute’s Digitisation Workplace, during which separate digitisation projects were presented. Shared problems were also identified and new methods for dealing them in the future were proposed. One of the key outcomes was the regular undertaking of applied research into monitor prototypes for digital cinematography in collaboration with EIZO Europe, verifying their application in practice, in combination with non-dedicated film players in DCP (Digital Cinema Package) format, giving restorers in Central Europe access to more affordable standardised film presentations on new compact displays instead of the relatively expensive projectors used for digital cinematography, while maintaining international norms and standards. During the workshop, also presented in collaboration with EIZO Europe were the results of experimental tests comparing various methods of film digitisation and restoration. There was also a presentation of the current situation in terms of film heritage in individual countries at the travelling exhibition of posters continuing in the National Technical Library and showcased until 31 December 2015, which looks at the value of shared Central European film heritage not just in terms of the historic value of art films, but also in their reminder of various contemporary events or important figures, or in uncovering the background to important moments in our histories, and also in finding out about previously unknown phenomena captured by film cameras.

During the workshop, also presented in collaboration with EIZO Europe were the results of experimental tests comparing various methods of film digitisation and restoration. There was also a presentation of the current situation in terms of film heritage in individual countries at the travelling exhibition of posters continuing in the National Technical Library and showcased until 31 December 2015, which looks at the value of shared Central European film heritage not just in terms of the historic value of art films, but also in their reminder of various contemporary events or important figures, or in uncovering the background to important moments in our histories, and also in finding out about previously unknown phenomena captured by film cameras.According to UNESCO, there are about 200 million hours of audiovisual material in the world, stored on various recording media (of which there are more than 2 200 million kilometres of cinematographic material on highly flammable nitrate film bases subject to decomposition). Roughly 100 million hours of various types of audiovisual material is located in Europe, and up to a third of this is stored in European film archives. Only a little over 1.04 million hours are stored here on film strips (the original negatives and copies). More than 85% of these cinematography works are according to estimates, however, commercially inaccessible. And according to a recent study by the Association of European Film Archives (ACE), a mere 1.5 % of all these films have been digitised so far to a quality allowing them to be shown in digital cinemas, although the situation differs greatly in individual European countries.

The accessibility of European films in our cinemas further worsened when traditional thirty-five millimetre projectors gradually began to disappear, to be replaced by digital projectors. This was followed by the demise of many film material and technology producers and laboratories, such as at Barrandov in June 2015. While in Western Europe the process of high quality film heritage digitisation has already begun, including through the interest of private producers, in the countries of Central Europe this began with the nationalised cinematography in the second half of the last decade (while in Poland and Slovakia the number of high-quality digitised feature films exceeds a hundred, here and in Hungary there are barely ten).

Like in other countries of the so-called former Eastern Bloc, in Central Europe (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland), insufficient means of currency exchange meant that between 1952 and 1998 the vast majority of colour films which were filmed on American Eastmancolor negatives were copied onto cheaper East German Orwocolor film stock, famed for its fluctuating quality. Film makers attempted to combat the poorer resolution, colour saturation and undesirable colour shift of these film copies (typically turning skin colour purplish, and giving natural green a blue tinge) by using special creative methods not just in laboratories but also during filming itself, such as adjusting the colour of actors’ makeup, costumes and props, and the use of special filters or lighting. Hungary began filming on Eastmancolor somewhat later at the end of the 1960s, and copies for cinemas were almost exclusively prepared on compatible colour Eastman, although usually of a lower quality than that used in the West. The incompatible system of reading Eastmancolour negatives, from which films were copied onto Orwocolor positives, was seen in the fluctuating sound quality. And like in the case of images, this know-how for high quality digital restoration is entirely foreign in Western Europe.

-

ORWO Region - Central European Film Heritage Digitization methodology presented at the XXIV. Association of Moving Image Archivists conference

10.10.2014In Central Europe, due to budgetary constraints and the inavailability of film stocks during time periods 1953 – 1998, a set of particular laboratory and creative techniques were applied whereby cinematographers shot color films on Eastman Kodak negative, but all positive elements and some intermediate were printed on East German ORWO film stock (or Agfa Wolfen before 1964).

Fuzzy and low resolution color negative film stock allowed shot cinemascope films mainly on Eastmancolor negative there. But Eastman color camera negatives printed on positive stock produced in Wolfen with slightly desatured colours were not always compatible. Therefore the results between what was captured on the original camera negative and what was screened in theaters differed greatly.

Green landscape appeared bluish and faces had purple tint. The filmmakers had to used altered lightening, make-up or set design adjustments top correct it. Different color dye layers order in Orwocolor versus Eastmancolor positive film prints degraded optical sound quality.

Therefore collaborative research project that demonstrates networking from digitisation to access and sharing best practices at work in Central European countries today, in which we are being explored film heritage digitisation workflow, were presentend at the international conference with very good positive feedback by the audience.

Great achivement of the Central European digitisation presentation were completed by the organizers’ invitation to the next year of international film archivist conference in Portland.

-

CLOSELY WATCHED TRAINS DIGITALLY RESTORED

5.7.2014New digital restoration of Academy awarded film CLOSELY WATCHED TRAINS (Ostře sledované vlaky, 1966) were presented at the International film festival in Karlovy Vary on the 5th of July 2014.

The premiere of the film directed by Jiří Menzel were preceded by the 'Closely Watched' Masterclass of the cinematographer Jaromír Šofr who actively supervised digital restoration of the film. Šofr presented methodology of digital film restoration based on Digital Restored Authorizate workflow developed during the present research which is operated by Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. The next experts presented their experiences with digital restoration in other Central European countries and the research project were mentioned as well.

The interview with cinematographer Jaromír Šofr focused to his long-lasting career and especially his masterpiece CLOSELY WATHED TRAINS for research project FROM DIGITISATION TO ACCESS were recorded as well.